Recommendation: reports on the search for missing hiker Bill Ewasko

How to find someone who has died in the wilderness.

Content warning: About an IRL death.

Today’s post isn’t so much an essay as a recommendation for two bodies of work on the same topic: Tom Mahood’s blog posts and Adam “KarmaFrog1” Marsland’s videos on the 2010 disappearance of Bill Ewasko, who went for a day hike in Joshua Tree National Park and dropped out of contact.

2010 – Bill Ewasko goes missing

Tom Mahood’s writeups on the search [Blog post, website goes down sometimes so if the site doesn’t work, check the internet archive]

2022 – Ewasko’s body found

ADAM WALKS AROUND Ep. 47 "Ewasko's Last Trail (Part One)" [Youtube video]

ADAM WALKS AROUND Ep. 48 "Ewasko's Last Trail (Part Two)" [Youtube video]

And then if you’re really interested, there’s a little more info that Adam discusses from the coroner’s report:

(I won’t be fully recounting every aspect of the story. But I’ll give you the pitch and go into some aspects I found interesting. Literally everything interesting here is just recounting their work, go check em out.)

Most ways people die in the wilderness are tragic, accidental, and kind of similar. A person in a remote area gets injured or lost, becomes the other one too, and dies of exposure, a clumsy accident, etc. Most people who die in the wilderness have done something stupid to wind up there. Fewer people die who have NOT done anything glaringly stupid, but it still happens, the same way. Ewasko’s case appears to have been one of these. He was a fit 66-year-old who went for a day hike and never made it back. His story is not particularly unprecedented.

This is also not a triumphant story. Bill Ewasko is dead. Most of these searches were made and reports written months and years after his disappearance. We now know he was alive when Search and Rescue started, but by months out, nobody involved expected to find him alive.

Ewasko was not found alive. In 2022, other hikers finally stumbled onto his remains in a remote area in Joshua Tree National Park; this was, largely, expected to happen eventually.

I recommend these particular stories, when we already know the ending, because they’re stunningly in-depth and well-written fact-driven investigations from two smart technical experts trying to get to the bottom of a very difficult problem. Because of the way things shook out, we get to see this investigation and changes in theories at multiple points: Tom Mahood has been trying to locate Ewasko for years and written various reports after search and search, finding and receiving new evidence, changing his mind, as has Adam, and then we get the main missing piece: finding the body. Adam visits the site and tries to put the pieces together after that.

Mahood and Adam are trying to do something very difficult in a very level-headed fashion. It is tragic but also a case study in inquiry and approaching a question rationally.

(They’re not, like, Rationalist rationalists. One of Mahood’s logs makes note of visiting a couple of coordinates suggested by remote viewers, AKA psychics. But the human mind is vast and full of nuance, and so was the search area, and on literally every other count, I’d love to see you do better.)

Unknowns and the missing persons case

Like I said, nothing mind-boggling happened to Ewasko. But to be clear, by wilderness Search and Rescue standards, Ewasko’s case is interesting for a couple reasons:

First, Ewasko was not expected to be found very far away. He was a 65-year-old on a day hike. But despite an early and continuous search, the body was not found for over a decade.

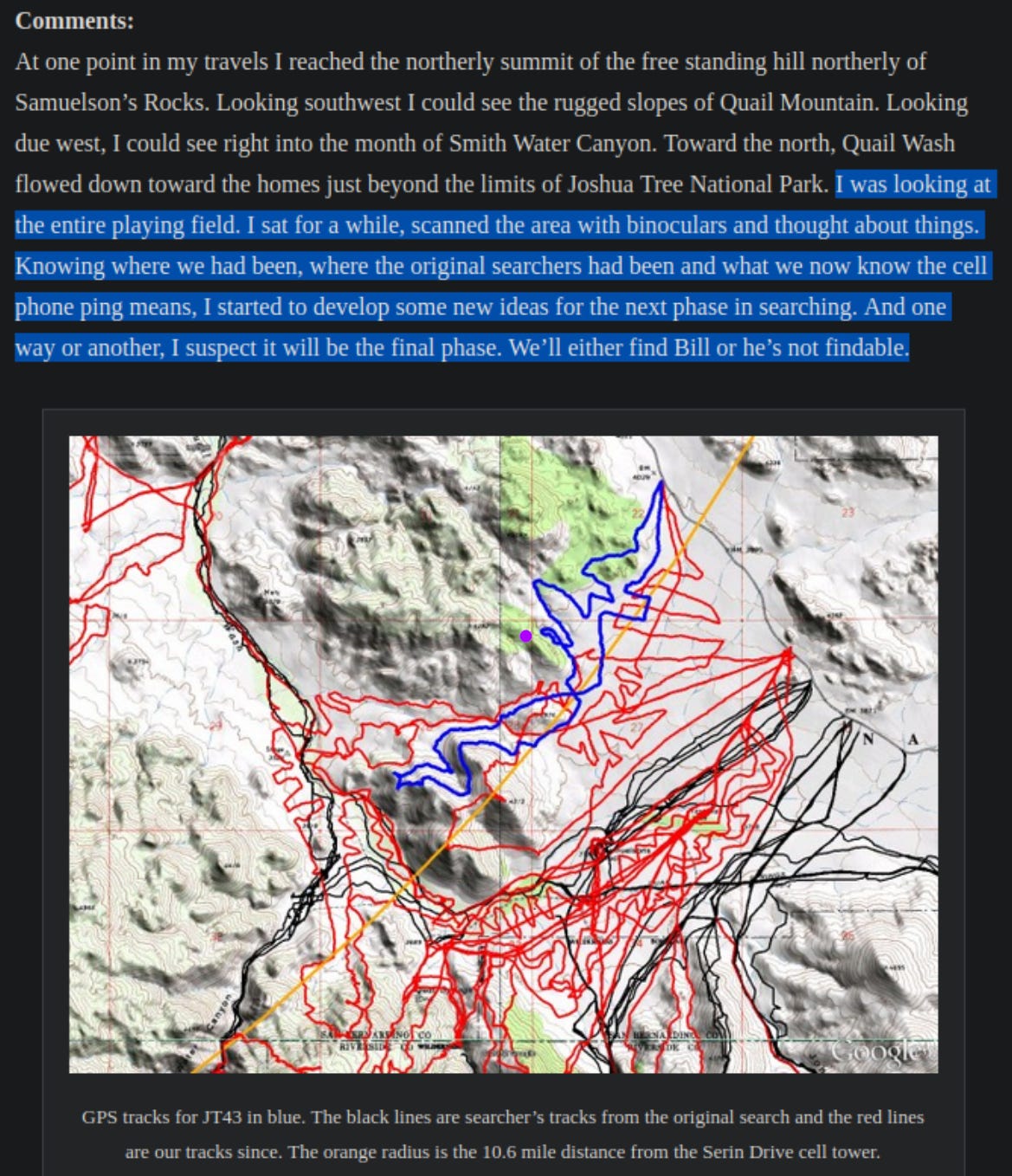

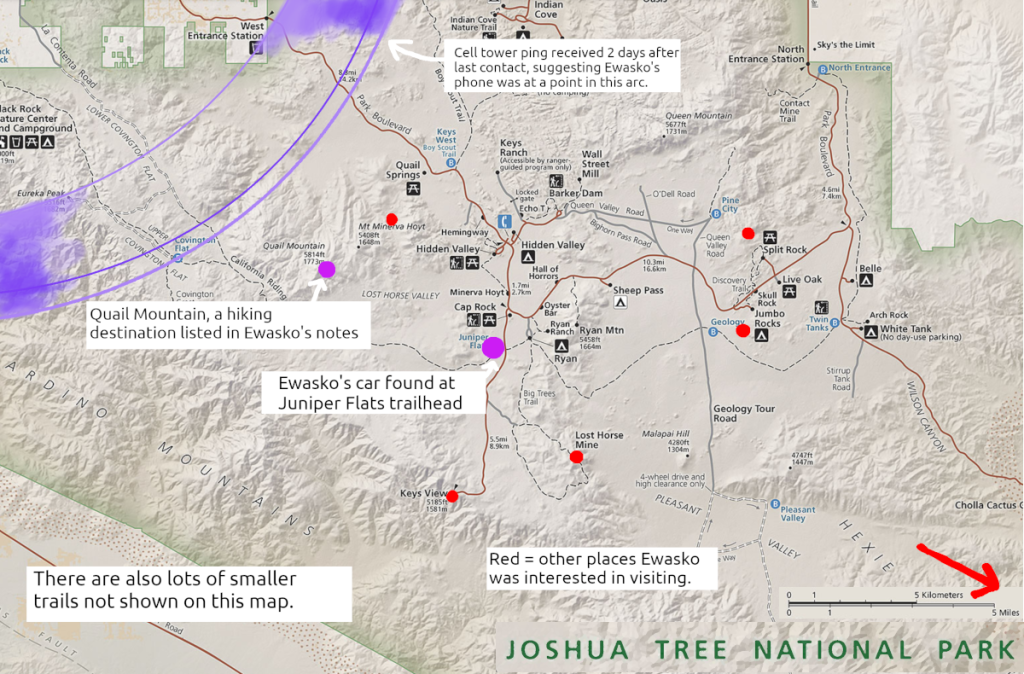

Second, two days after he failed to make a home-safe call to his partner and was reported missing, a cell tower reported one ping from his cell phone. It wasn’t enough to triangulate his location, but the ping suggested that the phone was on in a radius of approximately 10.6 miles around a specific cell tower. The nearest point of that radius was, however, miles in the opposite direction from the nearest likely trail destination to Ewasko’s car - from where Ewasko ought to be.

If you’ve spent much time in wilderness areas in the US, you know that cell coverage is findable but spotty. You’ll often get reception on hills but not in valleys, or suchlike. There’s a margin for error on cell tower pings that depends on location. Also, in this case, Verizon (Ewasko’s carrier) had decent coverage in the area – so it’s kind of surprising, and possibly constrains his route, that his cell phone only would have pinged once.

All of this is very Bayesian: Ewasko’s cellphone was probably turned off for parts of his movement to save battery (especially before he realized he was in danger), maybe there was data that the cell carrier missed, etc, etc. But maybe it suggests certain directions of travel over others. And of course, to have that one signal that did go out, he has to have gotten to somewhere within that radius – again, probably.

How do you look for someone in the wilderness?

Search and rescue – especially if you are looking for something that is no longer actively trying to be found, like a corpse – is very, very arduous. In some ways, Joshua Tree National Park is a pretty convenient location to do search and rescue: there aren’t a lot of trees, the terrain is not insanely steep, you don’t have to deal with river or stream crossings, clues will not be swept away by rain or snow.

But it’s not that simple. The terrain in the area looks like this:

There are rocks, low obstacles, different kinds of terrain, hills and lines of sight, and enough shrubbery to hide a body.

A lot of the terrain looks very similar to other parts of the terrain. Also dotted about are washes made of long stretches of smooth sand, so the landscape is littered with features that look exactly like trails.

Also, environmentally, it’s hot and dry as hell, like “landscape will passively kill you”, and there are rattlesnakes and mountain lions.

When a search and rescue effort starts, they start by outlining the kind of area in which they think the person might plausibly be in. Natural features like cliffs can constrain the trails, as can things like roads, on the grounds that if a lost person found a road, they’d wait by the road.

You also consider how long it’s been and how much water they have. Bill Ewasko was thought to have three bottles of water on him – under harsh and dry circumstances, that water becomes a leash, you can only go so far with what you have. A person on foot in the desert is limited in both time and distance by the amount of water they carry; once that water runs out, their body will drop in the area those parameters conscribe.

Starting from the closest, most likely places and moving out, searchers first hit up the trails and other clear points of interest. But once they leave the trail? Well, when they can, maybe they go out in an area-covering pattern, like this:

But in practice, that’s not always tenable. Maybe you can really plainly see from one part to another and visually verify there’s nothing there. Maybe this wouldn’t get you enough coverage, if there are obstacles in the way. There are mountains and cliff faces and rocky slopes to contend with.

Also, it’s pretty hard to cover “all the trails”, since they connect to each other, and someone is really more likely to be near a trail than far away from a trail. Or you might have an idea about how they would have traveled – so do you do more covering-terrain searching, or do you check farther-out trails? In this process, searchers end up making a lot of judgment calls about what to prioritize, way more than you might expect.

You end up taking snaky routes like this:

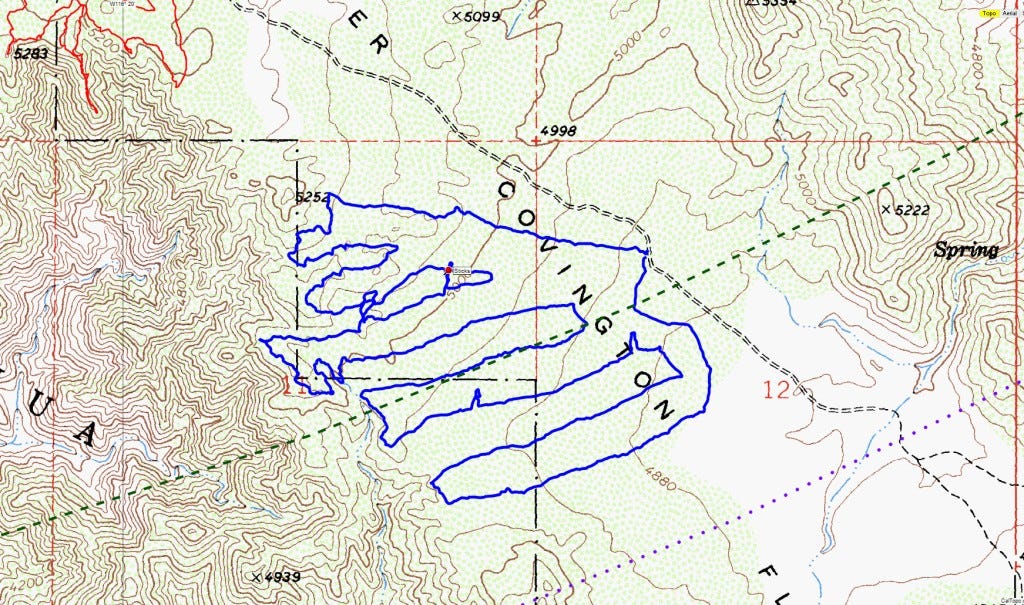

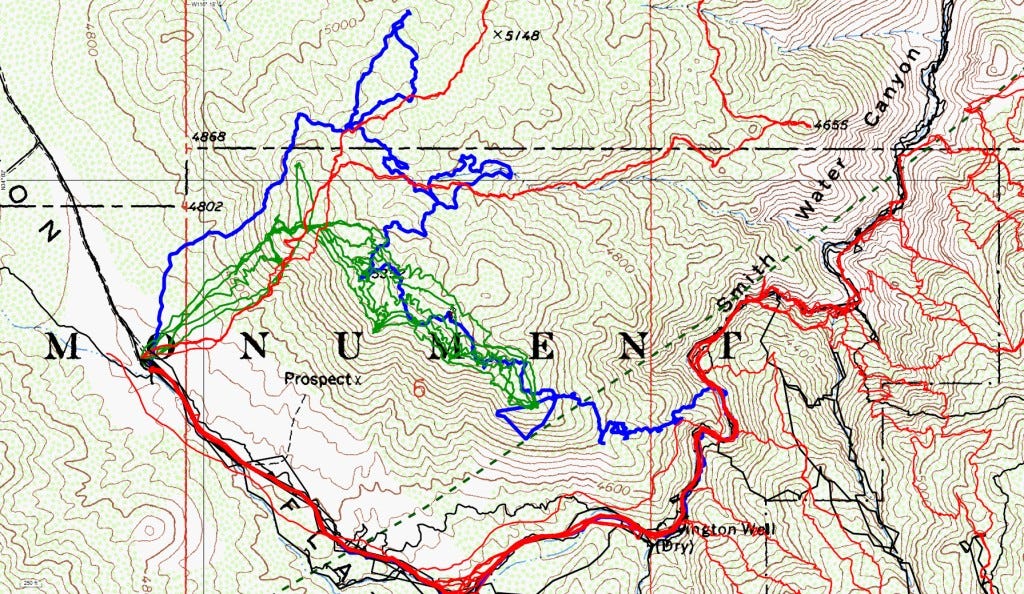

The initial, official Search and Rescue was called off after about a week, so the efforts Mahood records – most of which he is doing himself, or with some buddies – constitute basically every search that happened. He posts GPS maps too, of that day’s travels overlaid on past travels. You see him work outward, covering hundreds of miles, filling in the blank spots on the map.

Mahood is really good at both being methodical and explaining his reasoning for each expedition he makes, and where he thinks to look. It’s an absolutely fascinating read.

43 expeditions in, in December 2012, Mahood writes this:

The purple dot is my addition. This is where Ewasko’s body was found in 2022. Mahood wrote this about the same trip where (as far as I can tell) he came the closest any searcher ever got to finding Ewasko. Despite saying it was the end game, Mahood and associates mounted about 50 more trips. Hindsight is heartbreaking.

Making hindsight useful

Hindsight haunts this story in 2024. It’s hard to learn about something like this and not ask “what could have stopped this from happening?”

I found myself thinking, sort of automatically, “no, Ewasko, turn around here, if you turn around here you can still salvage this,” like I was planning some kind of cross-temporal divine intervention. That line of thinking is, clearly, not especially useful.

Maybe the helpful version of this question, or one of them, is: If I were Ewasko, knowing what Ewasko knew, what kind of heuristics should I have used that would have changed the outcome?

The answer is obviously limited by the fact that we don’t know what Ewasko did. There are some specifics, like that he didn’t tell his contacts very specific hiking plans. But he was also planning on a day hike at an established trailhead in a national park an hour outside of Palm Springs. Once he was up the trail, you’ll have to watch Adam’s video and draw your own conclusions (if Adam is even right.)

Mahood writes: “People seldom act randomly, they do what makes sense to them at the time at the specific location they are at.”

And Adam says: “Most man-made disasters don’t spring from one bad decision but from a series of small, understandable mistakes that build on one another.”

Another question is: If I were the searchers, knowing what the searchers know, what could I have done differently that would have found the body faster?

Knowing how far away the body was found and the kind of terrain covered, I’m still out on this one.

How deep the search got

Moving parts include:

Concrete details about Ewasko (Ewasko’s level of fitness, his supplies, down to the particular maps he had, what his activities were earlier in the day)

Ewasko’s broader mindset (where he wanted to go at the outset, which tools he used to navigate trails, how much HE knew about the area)

Ewasko’s moment-to-moment experience (if he were at a particular location and wanted to hurry home, which route would he take? What if he were tired and low on water and recognized he was in an emergency? What plans might he make?) (This ties into the field of Search and Rescue psychology – people disoriented in the wilderness sometimes make predictable decisions.)

Physical terrain (which trails exist and where? How hard is it to get from places to place? What obstacles are there)

Weather (how much moonlight was there? How hard was travelling by night? How bad was the daytime heat?)

Electromagnetic terrain (where in the park has cell service?)

Electromagnetic interpretation (How reliable is one reported cell phone ping? If it is inaccurate, in which ways might it be inaccurate?)

Other people’s reports (the very early search was delayed because a ranger apparently just repeatedly didn’t see or failed to notice Ewasko’s car at a trailhead, and there were conflicting reports about which way it was parked. According to Adam and I think Mahood, it now seems now like the car was probably there the entire time it should have been, and it was probably just missed due to… regular human error. But if this is one of the few pieces of evidence you have, and it looks odd – of course it seems very significant.)

The search evolving over time (where has been looked in what ways before? And especially as the years pass on – some parts of the terrain are now extremely well-searched, not to mention are regularly used by regular hikers. What are the changes one of these searches missed somewhere, vs. that Ewasko is in a completely new part of the territory?)

I imagine that it would be really hard to choose to carry on with something like this. In this investigation, there was really no new concrete evidence between 2010 and 2022. As Mahood goes on, in each investigation, he adds the tracks to his map. Territory fills in – big swathes of trails, each of them. New models emerge, but by and large the only changing detail is just that you’ve checked some places now, and he’s somewhere you haven’t checked. Probably.

A hostile information environment

Another detail that just makes the work more impressive: Mahood is doing all these investigations mostly on his own, without help and with (as he sees it, although it’s my phrasing) dismissal and limited help from Joshua Tree National Park officials. The reason Mahood posted all of this on the internet was, as he describes it, throwing up his hands and trying to crowd-source it, asking for ideas.

Then after that - The internet has a lot of interested helpful people – I first ran into Mahood’s blog months ago via r/RBI (“Reddit Bureau of Investigation”) or /r/UnsolvedMysteries or one of those years ago. I love OSINT, I think Mahood doing what he did was very cool. But also on those sites and also in other places there are also a lot of out-there wackos. (I know, wackos on the internet. Imagine.) In fact there’s a whole conspiracy theory community called Missing 411 about unexplained disappearances in national parks, which attributes them vaguely to sinister and/or supernatural sources. I think that’s all probably full of shit, though I haven’t tried to analyze it.

Anyway, this case attracted a lot of attention among those types. Like: What if Bill Ewasko didn’t want to be found? What if someone wanted to kill him? What if the cellphone ping was left by as an intentional red herring? You run into words like “staged” or “enforced disappearance” or “something spooky” in this line of thought, so say nothing of run-of-the-mill suicide.

Look, we live in a world where people get kidnapped or killed or go to remote places to kill themselves sometimes, the probability is not zero. Also – and I apologize if this sounds patronizing to searchers, I mean it sympathetically – extended fruitless efforts like this seem like they could get maddening, that alternative explanations that all your assumptions are wrong would start looking really promising. Like you’re weaving this whole dubious story about how Ewasko might have gone down the one canyon without cell reception, climbing up and down hills in baking heat while out of water and injured - or there’s this other theory, waving its hands in the corner, going yeah, OR he’s just not in the park at all, dummy!

Its apparent simplicity is seductive.

Mahood apparently never put much stock in these sort of alternate models of the situation; Adam thought it was seriously likely for a while. I think it’s fair to say that “Ewasko died hiking in the park, in a regular kind of way” was always the strongest theory, but it’s the easiest fucking thing in the world for me to say that in retrospect, right? I wasn’t out there looking.

Maps and territories

Adam presents a theory about Ewasko’s final course of travel. It’s a solid and kind of stunning explanation that relies on deep familiarity with many of the aforementioned moving factors of the situation, and I do want you to watch the video, so go watch his video. (Adam says Mahood disagrees with him about some of the specifics – Mahood at present hasn’t written more after the body was found, but he might at some point, so keep an eye out.)

I’ll just go talk a little about one aspect of the explanation: Adam suspects Ewasko got initially lost because of a discrepancy between the maps at the time and the on-the-ground trail situation. See, multiple trails run out of the trailhead Ewasko parked at and through the area he was lost in, including official park-made trails and older abandoned Jeep trails.

Adam believes that partly as a result of the 1994 Desert Protection Act, Joshua Tree National Park was trying to promote the use of their own trails, as an ecosystem conservation method. Ewasko believes that Joshua Tree issued guidance to mapmakers to not mark (or de-prioritize marking) trails like the old Jeep roads, and to prioritize marking their official trails, some of which were faint and not well-indicated with signage.

Adam thinks Ewasko left the parking lot on the Jeep road – which, to be fair, runs mostly parallel to the official trail, and rejoins to it later. But he thinks that Ewasko, when returning, realized there was another parallel trail to the south and wanted to take a different route back, causing him to look for an intersection. However, Ewasko was already on the southern trail, and the unlabeled intersection he saw was to another trail that took him deeper into the wilderness – beginning the terrible spiral.

Think of this in terms of Type I and Type II errors. It’s obvious why putting a non-existent trail on a map could be dangerous: you wouldn’t want someone going to a place where they think there is a trail, because they could get lost trying to find it. It’s less obvious why not marking a trail that does exist could be dangerous, but it may well have been in this case, because it will lead people to make other navigational errors.

Endings

The search efforts did not, per se, “work”. Ewasko’s body was not found because of the search effort, but by backpackers who went off-trail to get a better view of the sunset. His body was on a hill, about seven miles northeast of his car, very close to the cellphone ping radius. He was a mile from a road.

In Adam’s final video, on Ewasko’s coroner’s report, Adam explaining that he doesn’t think he will ever learn anything else about Ewasko’s case. Like, that he could be wrong about what he thinks happened or someone may develop a better understanding of the facts, but there will be no new facts. Or at least, he doubts there will be. There’s just nothing left likely to be found.

There are worse endings, but “we have answered some of our questions but not all of them and I think we’ve learned all we are ever going to learn” has to be one of the saddest.

Like I said, I think the searchers made an incredible, thoughtful effort. Sometimes, you have a very hard problem and you can’t solve it. And you try very hard to figure out where you’re wrong and how and what’s going on and what you do is not good enough.

These reports remind me of the wealth of material available on airplane crashes, the root cause analyses done after the fact. Mostly, when people die in maybe-stupid and sad accidents, their deaths do not get detailed investigations, they do not get incident reviews, they do not get root cause analyses.

But it’s nice that sometimes they do.

If you go out into the wilderness, bring plenty of water. Maybe bring a friend. Carry a GPS unit or even a PLB if you might go into risky territory. Carry the 10 essentials. If you get lost, think really carefully before going even deeper into the wilderness and making yourself harder to find. And tell someone where you’re going.

Crossposted to: eukaryotewritesblog.com | Substack | LessWrong